As It Happens, Not Next to “Godliness”

I’ve just completed reading Jessica Snyder Sachs’ fascinating Good Germs, Bad Germs: Health and Survival in a Bacterial World, a rather eye-opening look at both the futility and danger of our modern war on germs.

I’m not a germophobe per se; in fact I’m personally somewhat filthy compared to many people I know. I did get really freaked over the swine flu that was making the rounds last year, but that was the result of both having read in-depth accounts of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 and my admittedly limited knowledge of biology, which is still broad enough that I recognized that any type of flu virus novel to humans could become a Very Bad Thing if it managed to get into even one human body at the same time another flu virus was residing there and the two started swapping genes. Even a relatively mild virus can become a killer when given the right human petri dish in which to mutate.

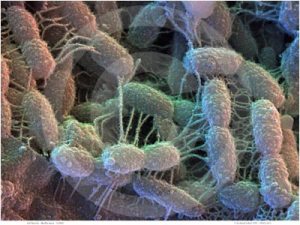

![bacteria[1]](https://3weirdsisters.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/bacteria1.jpg?w=300&h=225) The same, of course, is true of bacteria. They are living organisms and like all life, they evolve and adapt to their environment. In the case of the human body, they’ve adapted so well that we each carry around an estimated 9 times as many bacteria in and on our persons as we have living cells in our bodies. We are, literally, biomes for bacteria. This carries both blessings and curses; blessings in that the bacteria in our intestinal tracts literally feed us – without their activity, we could not break down food into its constituent nutrients for absorption. The curses are of course well-known and recognized – the wrong bacteria can kill us, either directly through damage to body systems, somewhat directly with their toxic byproducts, or indirectly by over-exciting our immune systems which end up destroying our own bodies. Given their ubiquity and ability to reproduce – and mutate – a million times faster than we can, probably any attempt to outflank the bad bacterial actors via development of antibiotics is predestined for failure.

The same, of course, is true of bacteria. They are living organisms and like all life, they evolve and adapt to their environment. In the case of the human body, they’ve adapted so well that we each carry around an estimated 9 times as many bacteria in and on our persons as we have living cells in our bodies. We are, literally, biomes for bacteria. This carries both blessings and curses; blessings in that the bacteria in our intestinal tracts literally feed us – without their activity, we could not break down food into its constituent nutrients for absorption. The curses are of course well-known and recognized – the wrong bacteria can kill us, either directly through damage to body systems, somewhat directly with their toxic byproducts, or indirectly by over-exciting our immune systems which end up destroying our own bodies. Given their ubiquity and ability to reproduce – and mutate – a million times faster than we can, probably any attempt to outflank the bad bacterial actors via development of antibiotics is predestined for failure.

That’s the bad news – and it gets worse: every time we use an antibiotic to fight off a bad bug, we also kill the good bugs, opening up new niches for colonization by bacteria that may be less helpful than the original inhabitants. We’ve made the problem worse with use of “antibacterial” cleansers such as products containing Triclosan which function more as an antibiotic than a true sanitizer. Bacteria have proved just as adept at mutating to be resistant to these cleansers as they have antibiotics. Worse yet, use of these products is making bacteria more resistant to the antibiotics we count on to fight off infection when a bad bug gets into the human body.

This is not to suggest that we’re worse off for modern sanitation – keeping cholera and E. coli out of the drinking water supply has had nothing but beneficial results. But we have become perhaps wimpier due to our isolation from the wide variety of bugs, both good and bad, to which humans for most of our evolutionary history were exposed on a regular basis. Most of us intuit this on one level or another, regardless of how obsessed we are with cleanliness – we know that animals both wild and domestic are exposed to more bacteria than we are. We don’t think twice about feeding food we’re not sure is still fit for human consumption to a dog or a cat – or at least we don’t if we’re sensible. Dogs eat crap – both their own and other animals’. Cats kill and eat rodents, ingesting along with them all the germs they carry. Most of us recognize that a burger or chicken that’s been in the fridge for a day or two beyond when we would eat it won’t faze an animal – they have “tougher guts” thanks to their closer daily contact with the microorganisms that abound in soil and elsewhere.

Mycobacterium vaccae is still under study, for everything from its apparent ability to boost immunity to leprosy and tuberculosis, to its seemingly beneficial effects on mood and learning ability.

The current hypothesis is that rates of auto-immune disorders such as allergies and asthma have skyrocketed in the past century for exactly this reason – we have sanitized the good bacteria which have beneficial effect on our immune systems out of our environment. Perhaps not coincidentally, rates for these types of disorders are lowest among farmers and others in rural areas, and almost unknown in many rural Third-World nations.

The new horizon in the war on bad germs seems to be identifying the good ones and encouraging them to take up residence. As Sachs details, various researchers are working with a wide variety of bacteria to advance treatment for everything from gingivitis to Crohn’s disease to rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and a host of other human ailments. In some cases they’re working to make the good bugs more effective colonizers; in others, they are genetically engineering bacteria to operate the on-off switch that causes auto-immune disorders.

Many obstacles remain, of course. Physicians still over-prescibe antibiotics, often for conditions where their use accomplishes nothing more than wiping out our beneficial microflora. Livestock are fed tons of antibiotics on feedlots which has led to soil bacteria that literally eat antibiotics for breakfast – not to mention outbreaks of deadly E. coli infection. And far too many of us seem to believe that we can sanitize ourselves to health, in the process accomplishing little more than aiding bacteria in gaining resistance to our only current line of defense against them while at the same time killing the good bugs and opening up niches for the bad ones in our homes and on our bodies.

So while it may be “filthy” for me to pet the cat and then eat without first washing my hands, or give her a kiss on the head after seeing her rolling in the dirt in the backyard, it hasn’t killed me yet. I’ll continue on with my nasty ways, eschewing the antibacterial soaps and cleaning supplies as well. As I like to joke, I’m the least medicated person in America, having taken only one course of antibiotics in over 20 years now, that being a relatively wimpy few doses of amoxicillan when the dentist suspected an infection that might require a root canal (fortunately, he was wrong – just an inflamed nerve from an ill-fitted crown). I’ll continue to spray down the raw produce with vinegar and hydrogen peroxide – with all the E. coli out there, you’d be foolish not to – as well as the countertops, because no bacteria adapted to causing illness in the human body will ever develop resistance to oxidation or over-acidity. But as for running to the doctor every time I have a sniffle, or nuking the house with Triclosan? No way. I want to keep my friendly bacteria alive and thriving.

As I like to joke, I’m the least medicated person in America, having taken only one course of antibiotics in over 20 years now

We’re probably neck and neck here. The last course of antibiotics I took was about seventeen years ago, chewable amoxicillan for an ear infection. They were big pink horse pills (I hate taking “grownup” pills), and they tasted like bubble gum.

It gets my goat that the harm of putting triclosan in hand soaps has been known for years — and yet these soaps are still on the market! WTH!

I hope they learn more about the good bugs.

If we had better health education in our schools, no one would buy them. Plain soap is just as effective at “disinfecting” skin as the anti-bacterial soaps are.

When I sold health education materials, one of the experiments we used to do with kids was one where they coated their hands with a light layer of petroleum jelly, then stuck them in a container of sand. The sand represented germs while the petroleum jelly was a stand-in for body oil. We’d have them shake hands with another kid to show how the “germs” spread through contact. Then we’d have them try to clean their hands by putting them under running water, which of course didn’t help. Last of all, we’d have them wash their hands with soap and water, to demonstrate how the soap breaks up the oil that binds bacteria to skin.

So not only are the anti-bacterial soaps and cleaning agents breeding tougher bugs, they’re also a complete waste of money. Plain soap does the job just as well, and for disinfecting, chlorine bleach or my favorite, a spray of hydrogen peroxide followed by a spray of vinegar (or vice-versa) are both cheaper and more effective.

Will plain soap get rid of John Boehner?

~

No. But it might return him to a normal color.

Contrary to popular belief I am a Microbiologist, and all that you have said is true, Jennifer. What percent is the Hydrogen peroxide you spray? I would go for 2 or 3 if it was me.

It is shameful of cleaning product companies to put out the antibiotic infused junk that they do and it will come back to bite us in the arse someday. Interesting thought: our house is pretty yuck compared to the operating theatre-like conditions of others yet our kids have no allergies and rarely get tummy bugs.I think people don’t realise what sort of bacterial soup we actually live in.

My fave story to illustrate that is when dog blood was being collected at a vet clinic near me. Overnight, in the fridge, the blood went from red to black and smelt bad. We isolated a Pseudomonas bug from it which grows best at 4 degrees Celsius.

What in the hell was it doing hanging around a vet surgery waiting for it’s chance? The answer is that they are all around us all the time. Wash your hands and clean up properly and you’ll be OK, you don’t need antibacterial BS.

That looks like a good book

It actually is a very good book – written for the layman but with lots of good information. Of course since it was published in 2008 the science has I’m sure moved on a bit since then.

I use the regular drugstore concentration of hydrogen peroxide, which I believe is 3%? Handy because the sprayer that came with my spray bottle fits it exactly – so I just leave it in the original container with the sprayer screwed on it. In any case, I of course rinse both it and the vinegar off of the produce after giving it a minute or so to do its thing. I don’t bother rinsing the counter after spraying, since neither the peroxide or the vinegar is toxic – I just wipe off the excess.

The current hypothesis is that rates of auto-immune disorders such as allergies and asthma have skyrocketed in the past century for exactly this reason – we have sanitized the good bacteria which have beneficial effect on our immune systems out of our environment.

To be pedantic about it,

——— PEDANTRY ALERT ————-

according to the hygiene hypothesis, the over-active arm of the immune system that leads to the asthma and the Crohn’s disease and so forth (the TH1 type immune response) is over-acting because it’s expecting nematodes that aren’t there.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helminthic_therapy

Not so much bacteria.

Overnight, in the fridge, the blood went from red to black and smelt bad.

Consume immediately once package is open.

You? A pedant herr doktor? NEVAR!!!!

Seriously though, nematodes alone are not the basis of the hygiene hypothesis, at least not according to Sachs’ book, which appeared to be pretty well researched. She did mention the beneficial aspect on the immune system that certain parasitic infections can have, but that was not the main thrust of the book, which was that there are also bacteria which appear to have the ability to modulate the TH1 immune response.

Just read the damn thing, ok? I’m not the expert here (“admittedly limited knowledge of biology”); I’m just commenting on a book I read which I thought was really interesting. You’d have to judge for yourself whether or not the theories reported on in the book have any merit or not. Even if you don’t agree with them, you’d probably still find it an interesting read.

Contrary to popular belief I am a Microbiologist, and all that you have said is true, Jennifer.

And here I was thinking your area of expertise was polychaetes.

Colour me surprised!

I’m a dental hygienist (and a former hydrogeologist with a masters in that but I no longer have the tolerance for teh crap that comes with working for consulting engineering firms, so I re-educated myself). The other place Triclosan is used is in Colgate toothpaste. I can always tell a Colgate user because inside their mouths the skin of their cheeks is sloughing off and forms a layer of whiteish, thready, dead skin. This leads me to believe that putting Triclosan in your mouth is rather a bad idea; not everyone reacts this way but when you see it, it’s from Triclosan. Just like putting it in handsoap, it is a stupid idea to put it in toothpaste; your mouth is full of germs and it is adapted to them being there so stop mucking with it and 99.9% of the time it will take care of itself just fine.

Ewwww!